The Crocodilian Body

Crocodilians have a "minimum exposure" posture in water, in which only the eyes, the cranial platform (overlying the brain), ears and nostrils lie above the waters' surface. All the sensory apparatus is thus exposed while the most of the snout length, and the bulk of the body, is hidden. To potential prey, the exposed areas of the head give little indication of the real size of the predator's body. This "minimum exposure" posture has been important to crocodilians throughout their evolution. Alligators, for example, have a broader snout than crocodiles, but, when in their "minimum exposure" posture in water, the two appear identical - the increased snout width is under the water. The changes in snout shape have not compromised this basic crocodilian posture, even though the two groups have been separated from each other for some 60 million years. Nasal Disc/Palatal Valve

Eyes

The eyes of crocodilians are very close together, and only 7 cm separates them in a 5 m long animal. They are oriented forward, resulting in binocular vision. This allows objects, especially potential prey, to be oriented precisely. Since the degree of overlap is small, crocodilians usually orient their head towards potential prey before attempting to approach it. EarsThe ear flaps are two rectangular flaps of tissue just below the edge of the cranial platform. There is an eardrum on either side, but the auditory canal that it covers, is continuous from one side of the head to the other. This appears to be yet another adaptation to assist in pinpoint orientation of potential prey. The high degree of development of the middle and inner ears indicates the effectiveness of crocodilian hearing over a wide range of frequencies (100-6000 Hz). Indeed the crocodilian ear is considered the most specialised within the Class Reptilia. BrainThe brain is relatively small, and lies directly below the midline of the cranial platform. Here, it is protected from the teeth of other crocodilians, and also lies in a position where it can heat rapidly when an animal is basking. This is important, because the brain must evaluate signals being received from the eyes, ears and nostrils, and like other reptiles, it probably functions more efficiently within a "preferred" temperature range. The "smell" or olfactory functions of the brain are particularly important, and prominent olfactory lobes extend forward to the nasal chambers. Sensory Pits

Jaws and TeethCrocodilian jaws are designed for grabbing and holding prey. The teeth are conical and designed to penetrate and hold, rather than cut and chew. In the Gharial, Tomistoma and other narrow-snouted species such as the Australian Freshwater Crocodile, the teeth can be very sharp indeed. The teeth of the upper and lower jaws intermesh perfectly when the jaws are closed, giving yet another means of holding firmly whatever they grasp. Teeth are often lost, but beneath each one is a replacement ready to fill the vacancy. The muscles that close the jaws are capable of generating enormous power. They are able to crush turtle shells with ease, and a large Saltwater Crocodile holding a pig's head can simply crush the skull by flexing the muscles from a "standing start". Yet the muscles that open the jaws have little strength. For example, a rubber band around the snout of a 2 m long crocodilian is sufficient to prevent it opening its mouth. In contrast, two strong people equipped with an assortment of levers are required to force open the mouth of a 1 m long crocodilian against the action of the muscles holding it shut. Although crocodilian jaws are capable of enormous power, they are also capable of delicate and gentle action. Large adults can pick up and roll unhatched eggs between their jaws, gently squeezing them until they hatch. Most species of crocodilian carry newly hatched young down to the water in their mouths. Internal OrgansThe internal organs of crocodilians are just as unique and specialised as the skeleton and external features. Crocodilians do not have a diaphragm separating the chest cavity from the viscera, and inhalation is achieved by the backward movement of the liver and other organs. The organs (heart, lungs, intestines, kidneys, etc.) have been modified to the crocodilian mode of existence. Heart

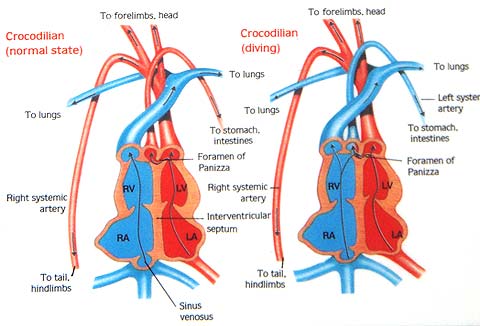

The crocodilian heart is quite unique. Other reptiles have a three-chambered heart (two atria and one partially divided ventricle). Crocodilians, like mammals and birds, have a four-chambered heart (two atria and two separate ventricles). In the three-chambered reptile heart, blood destined for the lungs (deoxygenated blood) can mix in the partly divided ventricle with blood destined to go out to the body (oxygenated blood from the lungs). In mammals and birds such mixing is impossible. But in crocodilians the blood vessels draining the left and right ventricles have an interconnecting aperture (the Foramen of Panizza) between them, which allows some mixing of blood, but outside of the ventricles. The mixing of blood can be advantageous to a diving reptile. StomachThe crocodilian stomach is a bag-like structure, with the inflow and outflow tracts next to each other. The capacity of the stomach is not very great, and so larger prey often cannot be eaten at the one sitting. An unusual feature of crocodilians is the tendency for them to retain hard, indigestible objects, such as stones, in the stomach. These "gastroliths" appear to help digestion, but they may also assist balance in water (hydroliths). Yet strangely, crocodiles in muddy areas, without access to stones, seem to do perfectly well without them. Scientists use this feature to their advantage, because small heavy items such as radio-transmitters stay in the stomach for long periods of time. The digestive enzymes in the stomach are particularly strong, and most bones and flesh are rapidly digested. On the other hand, hair and other keratinous substances (eg turtle shell), and chitin (eg insect cuticle), are broken down very slowly. Hair sometimes accumulates as “hairballs” within the stomach, and may later be regurgitated. TongueCrocodilians have a fleshy tongue that is attached along its length between the lower jaws. Lingual glands in the posterior part of the tongue are actually salt glands, which excrete excess salt when the animals are in highly saline environments. The salt glands are more developed in "true" crocodiles than in alligators and caimans, which have led researchers to postulate that the "true" crocodiles originated from a marine ancestor, whereas alligators and caimans may have evolved from a freshwater ancestor. Scales

The vertical scales along the tail (scutes) are hardened, but do not contain bone. The tail scutes increase the surface area of the tail substantially, and almost certainly play a role in swimming efficiency. They also have a good blood supply, and are sites of heat exchange between the animal and its environment. Sources: G. Webb and C. Manolis (1989): “Crocodiles of Australia” (Reed Books: Sydney); K. Richardson, G. Webb and C. Manolis (2000): “Crocodiles: Inside and Out” (Surrey Beatty and Sons: Sydney). |

Email CSG

Email CSG In general, the body form of crocodilians is "lizard-like". They have a long tail and the limbs are short and straddled sideways from the body rather than being erect beneath it, as in mammals. The elongated snout of crocodilians is probably one of their most distinctive features. The head is typically one seventh of the total body length, regardless of whether the species has a narrow or broad snout. The shape of the head is intimately associated with the way crocodilians position themselves in water.

In general, the body form of crocodilians is "lizard-like". They have a long tail and the limbs are short and straddled sideways from the body rather than being erect beneath it, as in mammals. The elongated snout of crocodilians is probably one of their most distinctive features. The head is typically one seventh of the total body length, regardless of whether the species has a narrow or broad snout. The shape of the head is intimately associated with the way crocodilians position themselves in water. The nasal disc on the tip of the snout contains two nostrils, each with a protective valve or flap at their opening. These lead into canals that pass through the bone of the snout, and open into the back of the throat. Along these canals are chambers in which "smell" is sensed - crocodilians have a very good sense of smell. A second route of breathing is through the mouth. At the back of the throat is a palatal valve that can be opened or closed. When basking on land with the mouth open, crocodilians breathe mostly through their mouth (the throat/palatal valve is open). When in water, the mouth is usually closed and they breathe mostly through their nostrils. When prey are being held in the water, the mouth may be open, but the palatal valve is closed, preventing water going down the throat - and breathing takes place through the nostrils.

The nasal disc on the tip of the snout contains two nostrils, each with a protective valve or flap at their opening. These lead into canals that pass through the bone of the snout, and open into the back of the throat. Along these canals are chambers in which "smell" is sensed - crocodilians have a very good sense of smell. A second route of breathing is through the mouth. At the back of the throat is a palatal valve that can be opened or closed. When basking on land with the mouth open, crocodilians breathe mostly through their mouth (the throat/palatal valve is open). When in water, the mouth is usually closed and they breathe mostly through their nostrils. When prey are being held in the water, the mouth may be open, but the palatal valve is closed, preventing water going down the throat - and breathing takes place through the nostrils. The eyes of crocodilians are specialised in a number of ways. Firstly, they are protected by a transparent eyelid that moves sideways across the eye when the animal submerges or attacks prey. Above and below the eye are the conventional eyelids, which cover the eye completely. The eyeballs themselves can be drawn into the eye sockets, presumably to avoid injury during attacks on prey or when fighting with other crocodiles. The eyes of crocodilians are focused for aerial distance viewing, and it is unlikely that their vision underwater is good.

The eyes of crocodilians are specialised in a number of ways. Firstly, they are protected by a transparent eyelid that moves sideways across the eye when the animal submerges or attacks prey. Above and below the eye are the conventional eyelids, which cover the eye completely. The eyeballs themselves can be drawn into the eye sockets, presumably to avoid injury during attacks on prey or when fighting with other crocodiles. The eyes of crocodilians are focused for aerial distance viewing, and it is unlikely that their vision underwater is good. As in many other nocturnal animals, the pupils close to a vertical slit in bright light and open to a full circle in the dark. At the back of the eyeball, behind the retina, is a thin layer of guanine crystals (retinal tapetum). Light passing through the retina is reflected back through it by these crystals. This image intensifying device, in combination with at least two different types of receptors in the retina, allow crocodilians to see better in low light situations. Alligators and caimans have colour vision, and it is likely that all crocodilians have it.

As in many other nocturnal animals, the pupils close to a vertical slit in bright light and open to a full circle in the dark. At the back of the eyeball, behind the retina, is a thin layer of guanine crystals (retinal tapetum). Light passing through the retina is reflected back through it by these crystals. This image intensifying device, in combination with at least two different types of receptors in the retina, allow crocodilians to see better in low light situations. Alligators and caimans have colour vision, and it is likely that all crocodilians have it. When a spotlight or torch is shone on a crocodilian at night, a red reflection from the eyes results. This "eyeshine" is a reflection of light from the retinal tapetum, and it can be seen from quite a distance away. Most crocodilian hunting takes place at night, using the "eyeshine" to detect the animal.

When a spotlight or torch is shone on a crocodilian at night, a red reflection from the eyes results. This "eyeshine" is a reflection of light from the retinal tapetum, and it can be seen from quite a distance away. Most crocodilian hunting takes place at night, using the "eyeshine" to detect the animal. The scales covering the head are very thin, relative to those of the rest of the body, and those along the sides of the jaws have pronounced sensory pits in them. These pits contain bundles of nerve endings and are involved in the detection of movement or vibrations in the water.

The scales covering the head are very thin, relative to those of the rest of the body, and those along the sides of the jaws have pronounced sensory pits in them. These pits contain bundles of nerve endings and are involved in the detection of movement or vibrations in the water. Replacement of teeth occurs roughly every 20 months, throughout life, but slows down as the animal gets older, and may stop altogether with the oldest and largest individuals. The number of teeth varies from 60 in the Dwarf Crocodile to 110 in the Gharial. Saltwater Crocodiles have 66 teeth, 18 on each side of the upper jaw and 15 on each side of the lower jaw.

Replacement of teeth occurs roughly every 20 months, throughout life, but slows down as the animal gets older, and may stop altogether with the oldest and largest individuals. The number of teeth varies from 60 in the Dwarf Crocodile to 110 in the Gharial. Saltwater Crocodiles have 66 teeth, 18 on each side of the upper jaw and 15 on each side of the lower jaw.

The skin of crocodilians is composed of a network of interconnected scales or scutes of various shapes and sizes. On the belly surfaces these scales tend to be square and flat, and it is the skin of this region that is most commonly used in the leather industry. The scales on the flanks and the neck tend to be round with a raised centre. Along the back and upper surfaces of the tail, the scales are raised in a very pronounced way.

The skin of crocodilians is composed of a network of interconnected scales or scutes of various shapes and sizes. On the belly surfaces these scales tend to be square and flat, and it is the skin of this region that is most commonly used in the leather industry. The scales on the flanks and the neck tend to be round with a raised centre. Along the back and upper surfaces of the tail, the scales are raised in a very pronounced way. Bone may be deposited within the scales as discrete and isolated blocks, called “osteoderms”. These are most pronounced along the back, and are responsible for the keeled shape of the back scales. These scales are supplied with a rich blood supply that transports heat back into the body when crocodilians bask. The extent to which bone is deposited in the belly scales varies between species and within the one species from different areas. The value of skins varies with the extent of osteoderms. The belly scales of caimans invariably have large osteoderms in them, and so the value of belly skins is greatly reduced. Saltwater Crocodiles never have osteoderms in the belly scales, and the skin of this species, when tanned, gives a uniformly coloured and smooth textured piece of leather - the skins of this species are the most highly prized of all crocodilians.

Bone may be deposited within the scales as discrete and isolated blocks, called “osteoderms”. These are most pronounced along the back, and are responsible for the keeled shape of the back scales. These scales are supplied with a rich blood supply that transports heat back into the body when crocodilians bask. The extent to which bone is deposited in the belly scales varies between species and within the one species from different areas. The value of skins varies with the extent of osteoderms. The belly scales of caimans invariably have large osteoderms in them, and so the value of belly skins is greatly reduced. Saltwater Crocodiles never have osteoderms in the belly scales, and the skin of this species, when tanned, gives a uniformly coloured and smooth textured piece of leather - the skins of this species are the most highly prized of all crocodilians. The bony scales along the back are the "armour", and some species are considered more heavily armoured than others. These scales protect, to a large degree, the delicate inner organs from injury during fights with other crocodiles, and tooth marks in them are reasonably common.

The bony scales along the back are the "armour", and some species are considered more heavily armoured than others. These scales protect, to a large degree, the delicate inner organs from injury during fights with other crocodiles, and tooth marks in them are reasonably common.