Crocodilian Capacity Building Manual HomeCROCODILIAN CAPACITY-BUILDING MANUAL

1. Introduction

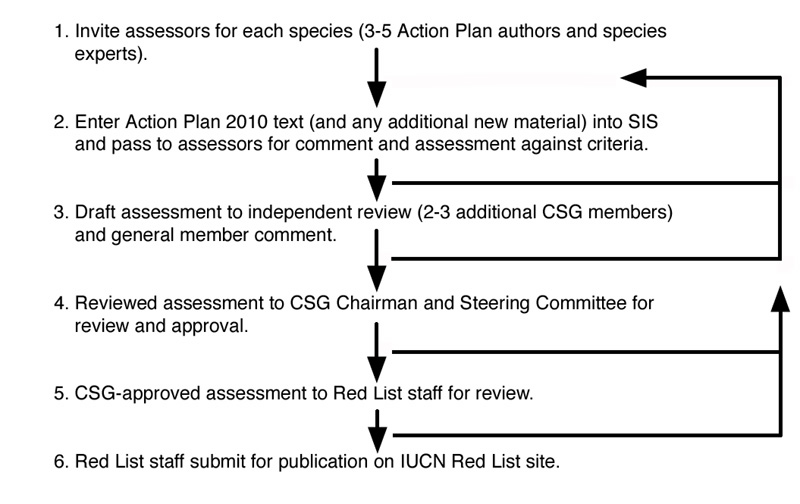

1.1. Purpose of document (Grahame Webb) 1.2. Brief history of crocodilian conservation and management 1.3. The IUCN Red List (Perran Ross) 2. Principles of Conservation and Management 2.1. Population recovery and conservation 2.2. Management Programs 2.3. Management (eg Introduction, goal, objectives, strategies for each section) 3.3. Ranching 2.3.2. Farming 2.3.3. Wild harvest 2.3.4. Problem/nuisance crocodile control 2.3.5. Human-Crocodile Conflict 2.3.6. Public education and awareness 2.3.7. Socio-economic factors 2.3.8. Monitoring/Field Techniques a. Survey b. Capture methods (Charlie Manolis) c. Handling d. Sampling e. Population analysis f. Tissue/DNA sampling and preservation (Matthew Shirley) g. Other 2.3.8. Captive husbandry 3. Legal 3.1. International - CITES requirements (Dietrich Jelden) 3.2. National - internal regulations(national-provincial law) - basic components and case studies. 3.3. Regional – example from West & Central Africa. 3.4. Law Enforcement 3.4.1. National 3.4.2. International (Dietrich Jelden) 4. Economics 4.1. Sustainable Use 4.1.1. Ranching 4.1.2. Wild Harvest 4.1.2.1. Commercial harvest 4.1.2.2. Sport hunting 4.1.3. Livelihoods (Alejandro Larriera) 4.2. Ecotourism 4.3. Ecological - valuing crocodilians 4.4. Commercial products 4.4.1. Skins 4.4.2. Meat 4.4.3. Other 5. Veterinary 5.1. Health and disease diagnosis and management (Paolo Martelli) 5.2. Animal care and use 5.3. Captive 5.3.1. Ranching and farming 5.3.2. Zoological collections (Kent Vliet) 5.4. Wild 5.5. Link to Veterinary Science on CSG website 1. Introduction (Grahame Webb) 1.1. Purpose of the Crocodilian Capacity Building Manual (Grahame Webb) 1.2. Brief History of Crocodilian Conservation and Management 1.3. The IUCN Red List (Perran Ross) The IUCN Red List is the authoritative list of globally threatened animals and plants, now on-line, fully searchable and listing more than 35,000 animals. The Red List has always been generated by species experts of the Species Survival Commission (SSC) specialist groups - like CSG. CSG used new criteria to assign Red List categories to all 23 crocodilians in 2002 and has re-evaluated several species since then, notably the Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus), Cuban crocodile (Crocodylus rhombifer), Mugger (C. palustris), Tomistoma (Tomistoma schlegelii) and Philippine crocodile (C. mindorensis). However, most CSG crocodilian assessments are unchanged and largely unexamined since the mid-late 1990s and are overdue for updates. From early, fairly informal beginnings in 1972, the list and the process that produces it has steadily become more objective, scientific and (unavoidably) more complex. The current IUCN process and how CSG intends to assess crocodilians for Red Listing is described here. Red List categories and criteria are now based on IUCN Red List categories and criteria Version 3.1 (2001). Species are assigned to one of 7 categories if, and only if, they meet just one of the criteria applying to any category. Three of the categories are familiar ‘threatened’ status (Vulnerable, Endangered and Critically Endangered). The other categories accommodate species that are not threatened (Least Concern, Near Threatened, Extinct in the Wild, and Extinct). The criteria for threatened species cover 5 broad indices of extinction risk: A. Reduction in population size B. Limited geographic range C. Small population size combined with other risk factors (decline, population structure) D. Extremely small population size E. Quantitative analysis indicating risk of extinction Each criterion has detailed components and sub-criteria and objective, quantitative thresholds. The terminology for Red List criteria is specific to this use and carefully defined. There are rules and Guidelines for applying the criteria and a large body of case history and precedent to guide their application. The Red List only considers all of a species throughout its global range, but there are additional criteria to adjust assessments of local or regional populations. All Red List assessments are now entered and processed through IUCN’s Species Information System (SIS) - an automated on-line data base for Red List assessment. These components are all very fully described in the Red List materials and guidelines. To apply these criteria to a species, an ‘assessment’ is performed. This is usually done by specialist groups or by specially convened Global Biodiverisity Assessment Workshops. Assessments undergo a procedure of drafting, review and evaluation, checking by IUCN Red List staff, and then publication on a roughly annual schedule (assessments completed by August of one year are published by May of the following year). Each specialist group (including CSG) established a “Red List Authority” (RLA) under the guidance of an RLA focal point to coordinate, review and submit its assessments. For CSG, the final authority for Red Listing crocodiles lies with the CSG Chairman operating with the CSG Steering Committee. The Chairman has designated Dr. Perran Ross to be the CSG's RLA focal point and coordinate our internal process. In consultation with the Chair and Steering Committee, Dr. Ross proposes small groups of ‘assessors’ who generate the raw material of each species assessment. Each assessment is then independently reviewed by 2-3 experts additional to the assessors. The reviewed assessments will then be approved by the Chair and passed to SSC Red List staff. They will perform their own review - largely to ensure correct application and interpretation of the criteria - and upon approval, pass the assessment into the publication stream. In 2010 the CSG completed and published on-line ‘Action Plans’ for each crocodilian species, and these summarize the most current information, threats and situation review. These Action Plans were the basis for the next round of crocodilian Red List Assessments and their authors will be invited to be the core group of ‘assessors’ for each species. The contents of each species action plan can be transferred (largely cut and paste) into the required modules of SIS. With information and coaching from the RLA focal point, assessors can determine which, if any, of the criteria are supported by the available data and which threatened category, or none, applies. This draft assessment then needs to be externally reviewed by additional experts to confirm both the data and the application and interpretation of the Criteria. After review the draft will pass to the CSG Chair and Steering Committee for their review and approval before submitting to IUCN Red List staff. IUCN staff will review again and may request additional information or changes from the assessors and RLA before accepting the assessment for publication at the next available opportunity. We may also use CSG meetings or dedicated workshops as opportunity arises to use the assembled expertise of CSG members to conduct an assessment.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) was established to regulate trade in species that are threatened by international trade. All crocodilians are listed on the Appendices of CITES, on either Appendix I and/or Appendix II. Wijnstekers (2011; English, French) details the evolution of CITES since 1975 when it entered into force. Transfer of crocodilian populations between the Appendices must be approved by the Conference of the Parties to CITES, and proposals must be submitted in accordance with Resolution Conf. 9.24 (CoP15) or Resolution Conf. 11.16 (Rev. CoP15)(ranching). Jelden (2004) provides an overview of key events within CITES that have impacted on crocodilians. Commercial international trade in Appendix-I listed crocodilians is prohibited, except through captive breeding from CITES-registered operations [Resolution Conf. 12.10 (Rev. CoP15)], and trade in Appendix-II species must demonstrate that trade is not detrimental to the survival of the species (ie non-detriment finding). Resolution Conf. 11.12 (Rev. CoP15) outlines the marking system for crocodilian specimens in trade. In some countries, crocodile farms produce hybrids between two different species. The marking of specimens derived from hybrids is specifically addressed in Resolution Conf. 11.12 (Rev. CoP15). However, the general issue of hybridization and its legal implications are covered by Resolution Conf. 10.17 (Rev. CoP14). The CITES Secretariat maintains a list of CITES-approved suppliers of tags for the identification of crocodilian skins, which are in compliance of Resolution Conf. 11.12 (Rev. CoP15). The list is regularly updated and communicated by a Notification (currently Notification No. 2009/048) to the Parties of the Convention. Control of trade in personal effects is covered by Resolution Conf. 13.7 (Rev. CoP14), which includes an exemption for four (4) crocodilian personal effects per person (Appendix-II species) from permitting requirements. However, some Parties may have stricter domestic measures than are required by CITES (Resolution Conf. 4.22 and Resolution Conf. 6.7), and not recognise this exemption of crocodilian personal effects. Statistics on international trade in crocodilian products are compiled by the UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC), which manages the searchable CITES Trade Database. Trends in crocodilian skin trade are regularly summarised (eg Caldwell 2010; Caldwell 2012).    References Caldwell, J. (2010). World Trade in Crocodilian Skins, 2006-2008. UNEP-WCMC: Cambridge. Download. Caldwell, J. (2012). World Trade in Crocodilian Skins, 2008-2010. UNEP-WCMC: Cambridge. Download. Jelden, D. (2004). Crocodilians and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Pp. 66-68 in Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 17th Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland. Download. Webb, G.J.W. (2004). Article IV of CITES and the concept of "non-detriment". Pp. 72-77 in Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 17th Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland. Download. Wijnstekers, W. (2011). The Evolution of CITES. 9th Edition. International Council of Game and Wildlife Conservation: Hungary. 937 pp. Download English, French or Spanish version. ------------------------------------------------ 2.3.7. xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Capture Methods Within any crocodilian management program there will invariably be a requirement to capture and handle animals. A range of direct and indirect methods are employed to capture crocodilians, based on a variety of factors, including body size, wariness, habitat type, etc. Cherkiss et al. (2009) provide a good overview of crocodilian capture methods, which include:

References Cherkiss, M.S., Fling, H.E., Mazzotti, F.J. and Rice, K.G. (2009). Counting and capturing crocodilians. CIR1451, IFAS Extension, University of Florida. Download. Hutton, J.M., Loveridge, J.P. and Blake, D.K. (1987). Capture methods for the Nile crocodile in Zimbabwe. Pp. 243-247 in Wildlife Management: Crocodiles and Alligators, ed. by G.J.W. Webb, S.C. Manolis and P.J. Whitehead. Surrey Beatty and Sons: Chipping Norton. Download. Kofron, C.P. (1989). A simple method for capturing large Nile crocodiles. African Journal of Ecology 27(3): 183-189. Mazzotti, F.J. and Brandt, L.A. (1988). A method of live-trapping wary crocodiles. Herpetological Review 19: 40-41. Murphy, T.M. Jr. and Fendley, T.T. (1973). A new technique for live trapping of nuisance alligators. Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Southeast Game and Fish Commission 27: 308-311. Murphy, T., Wilkinson, P., Coker, J. and Hudson, M. (1983). The alligator trip snare: a live capture method. South Carolina Wildl. and Marine Resour. Dep.: Columbia. Download. Walsh, B. (1987). Crocodile capture techniques in the Northern Territory of Australia. Pp. 249-252 in Wildlife Management: Crocodiles and Alligators, ed. by G.J.W. Webb, S.C. Manolis and P.J. Whitehead. Surrey Beatty and Sons: Chipping Norton. Download. Webb, G.J.W. and Messel, H. (1977). Crocodile capture techniques. Journal of Wildlife Management 41: 572-575. Download. Wilkinson, P.M. (1994). A walk-through snare design for the live capture of alligators. Pp. 74-76 in Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 12th Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland. Download. Woodward, A.R. and David, D.N. (1994). Alligators (Alligator mississippiensis). In The Handbook: Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage. Internet Center for Wildlife Damage Management, University of Nebraska: Lincoln. Download. ------------------------------------------------ 5.3.2. Zoological Collections Zoos, aquaria and other “living” institutions are deeply involved in the conservation of endangered crocodilians. In recognition of the important roles that these institutions play in conservation, research and education, the CSG established a Zoos thematic group within its organizational structure. The group includes a few dozen members of the CSG experienced in captive management, zoo husbandry, captive breeding and reintroduction. Those seeking information or wishing to communicate with this group may contact the CSG Vice-chair of the Zoos group, Dr. Kent Vliet (kvliet@ufl.edu). Exhibition of captive crocodilians brings these animals and their conservation dilemmas into the public conscience. Zoo specimens serve as ambassadors for their species in the wild. Through visitation to zoos and aquaria, zoo education and outreach programs have the ability to reach millions of people worldwide each year. While the majority of these visitors live in urban areas and regions of the world outside the native range of crocodilians, zoo interpretation and education programs can raise the awareness of the importance of crocodilians in the natural world and encourage support and participation in programs necessary for the long-term survival and conservation of crocodiles. People must be inspired and motivated to care about and understand the threats that animals face in the wild. Thus, the actions of zoos can direct public participation and financial support to conservation projects of endangered and critically endangered crocodilians. Access to captive animals by scientists facilitates research and expands our knowledge of the biology and behavior of the group. Although crocodilians have been held in captivity since at least ancient Roman times, historically, zoo collections were simply menageries of mixed species. It was only really in the late-1960s and 1970s when zoos first began keeping crocodilians in breeding pairs and captive reproduction was first recorded. Since that time, all living species of crocodilians have been reproduced under captive circumstances. Zoological collections in the USA include virtually all of the living crocodilian species, as do those in Europe. Conservation programs in zoos extend far beyond promoting the preservation of endangered species through ex-situ captive breeding programs. There is growing awareness of the important role ex-situ conservation plays in overall conservation strategies (Pritchard et al. 2011). And, with an increasing rate of global extinctions, continued habitat loss and the, as yet not fully understood, impact of global climate change, this role is certain to become more important in the future. Captive breeding populations in zoos may serve as assurance colonies or genetic reservoirs in case of an ultimate loss of the wild populations. There are relatively few, but highly significant, cases in which zoo animals have made enormous contributions to the initiation of recovery of critically depleted wild stocks. For instance, in the 1970s, an adult male Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) from the Frankfurt Zoo, transported to India to assist an intensive captive breeding effort, became an important founder in the effort to head-start and reintroduce Gharial into wild sanctuaries. Managed, cooperative breeding programs in zoos are designed to maintain the genetic diversity of small, captive breeding populations. This attention to heredity proves invaluable when captive populations are needed as a source for reintroduction programs. The Chinese alligator (Alligator sinensis) Species Survival Plan (SSP) in Association of Zoos and Aquaria (AZA) zoos in North America has managed a cooperative breeding program for this species for almost three decades. The known genetic pedigree of these animals made them attractive to wildlife officials in southern China and Chinese alligators from the SSP were imported into China for a reintroduction effort on Chongming Island, near Shanghai. Within zoos, there is significant linking between in-situ and ex-situ conservation programs. The Cuban crocodile (Crocodylus rhombifer) faces the possibility of being genetically swamped in the wild due to hybridization with the sympatric populations of American crocodile (C. acutus). It is quite conceivable that no genetically pure C. rhombifer will remain in the wild in the next few decades. There has been a managed breeding program for the Cuban crocodile in AZA institutions in the USA for many years. European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) institutions in Europe are initiating a similar program. These captive breeding programs, plus captive populations of genetically pure crocodiles in Cuba, may be the only long-term hope for continued existence of this beleaguered species. The CSG includes several taxon-specific conservation programs that bring experts from academic institutions, wildlife authorities, zoos and aquaria, and other related professions to focus their talents on conservation problems of critically endangered crocodilian species. The CSG Tomistoma Task Force has drawn great support of expertise from the zoo community in its efforts to protect the Tomistoma (Tomistoma schlegelii) and its habitats. The Chinese Alligator Fund initially grew from the efforts of zoo professional and private individuals interested in helping the plight of this species. The CSG has a Chinese Alligator Working Group which focuses its efforts on identifying potential release sites of captive-bred alligators and helping to establish new reintroduced populations. The World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA) consists of more than 250 zoos and aquaria as institutional members, and has advanced several conservation strategies to implement conceptual development of practices and strategies for zoos and aquaria to adopt. Conservation Strategies are published in multiple languages to communicate the message of the strategies and to facilitate promotion and adoption to a broader audience. Through a series of workshops organized by WAZA in 2000/2001 a strategy was developed to increase WAZA participation in in-situ conservation. The strategy involves the branding of conservation projects or programs by WAZA, after these projects have met sets of endorsement criteria. Since this time, WAZA branding of projects has taken on increasing clout within the conservation community. Branding of conservation priorities in the Mesangat wetlands of East Kalimantan were instrumental in the establishment of the EAZA/IUCN SSC Southeast Asia Campaign mentioned below. The Mabuwaya Philippine Crocodile Conservation Program also has been WAZA-branded as proposed by Chris Banks (Melbourne Zoo). In partnership with the EAZA and the European section of the IUCN-SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (CBSG), WAZA is establishing a World Zoo and Aquarium Conservation Database. This database currently catalogues more than 900 in-situ conservation projects supported by the international zoo community. AZA is a professional organization of more than 6000 institutions, individuals and vendors from all over the world. Since 1924, rigorous accreditation standards ensure the professional conduct and standards of AZA institutions and partner organizations. AZA-accredited institutions provide support for research and conservation projects worldwide. In 2010 alone, AZA facilities provided $US130 million in support to conservation projects in more than 100 countries. Species Survival Plans (SSP) for many of the world’s most threatened and endangered species provide coordinated captive breeding programs, in-situ conservation programs, habitat preservation and restoration, public education and research. SSPs for crocodilian species are managed by the AZA Crocodilian Advisory Group (CAG), the first Taxon Advisory Group within the AZA. The CAG maintains studbooks and SSP programs for the most endangered crocodilians species (Alligator sinensis, Crocodylus rhombifer, C. siamensis, C. mindorensis, C. intermedius, C. (Mecistops) cataphractus, Gavialis gangeticus, Tomistoma schlegelii). ISIS, the International Species Information System, maintains an extensive database of animal species held in zoos and aquariums, and details of their zoo environments. This system, the Zoological Information Management Systems (ZIMS), links records from more than 800 member zoos and aquaria in at least 80 countries, and includes comprehensive data on more than 2.6 million captive animals of 10,000 species. EAZA is a professional association of zoos and aquariums in Europe, with more than 345 member institutions from 41 countries. The EAZA manages cooperative breeding programs. The Endangered Species Program (ESP), similar to the SSP programs of the AZA, has intensive, cooperative, population management plans for individual species. Each has a coordinator and a species committee, which make pairing, breeding and transfer recommendations designed to promote and maintain the genetic diversity of the captive population. RRPs include only specimens kept in EAZA institutions. There is an EEP for C. mindorensis and one was previously maintained for A. sinensis. European studbook (ESB) programs are less intensive management plans than the EEPs. A studbook keeper maintains records of all specimens in the program and all life events, including data on births, deaths, transfers, etc. ESBs exist for C. rhombifer and T. schlegelii, plus Osteolaemus tetraspis is being considered. ESBs may include specimens from non-EAZA institutions and from some highly qualified private collections. The EAZA has a single Taxon Advisory Group for all reptiles. Fabian Schmidt (fschmidt@zoo-leipzig.de), Zoo Leipzig, oversees the crocodilian matters in this. The Southeast Asia Campaign, a joint venture between the EAZA and IUCN/SSC, raises public awareness and funds for the conservation of biodiversity in Southeast Asia. One project in this campaign, the Conservation of the Mesangat wetland in East Kalimantan, is of extreme importance to the conservation of two endangered species of crocodilians - T. shlegelii and C. siamensis. Both species occur in Mesangat Lake and the vast peat swamp forest surrounding it, an area salvaged from development from a local palm oil company and now proposed for permanent conservation by YASIWA - the Equatorial Conservation Foundation of Indonesia (www.yasiwa.org). International Zoo Educators Association (IZE) members dedicate themselves to improving the impact of conservation education programs in zoos and aquariums. The CBSG is a network of conservation professionals from around the world committed to developing scientifically-based, cooperative conservation programs aimed at saving threatened species. The CBSG has developed workshops aimed at gathering essential data for the scientific analysis of conservation strategies directed at endangered species. These Population and Habitat Viability Assessment (PHVA) workshops bring together attendees with a range of knowledge on biology, ecology, habitat, reproduction, genetics, GIS and land use patterns. Computer models use data compiled from these sources to evaluate the potential impact of various management strategies on the risk of population decline or extinction of the species. Other regional zoo associations exist, too numerous to list all: * British & Irish Association of Zoos & Aquariums (BIAZA) * Canadian Association of Zoos and Aquariums (CAZA) * Mexican Association of Zoos & Aquariums (AZCARM) * Pan African Association of Zoological Gardens, Aquaria & Botanical Gardens (PAAZAB) * Sociadade de Zoologicos do Brasil (SZB) * South Asian Zoo Association for Regional Cooperation (SAZARC) * South East Asian Zoo Association (SEAZA) * Zoo and Aquarium Association (ZAA) References Acharjyo, L.N. (1999). Role of Nandan Kanan Zoological Park in the conservation of Indian crocodilians. ENVIS (Wildl. & Prot. Areas) 2: 1-4. Arteaga, A., I. Cañizales, et al. (1996). Taller de analysis de la viabilidad poblacional y del habitat (PHVA) del Caiman Orinoco (Crocodylus intermedius). Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN, USA, Brazaitis, P. and Abene, J. (2008). A history of crocodilian science at the Bronx Zoo, Wildlife Conservation Society. Herpetol. Rev. 39(2): 135-148. Conde, D.A., Flesness, N., Colchero, F., Jones, O.R. and Scheuerlein, A. (2011). An emerging role of zoos to conserve biodiversity. Science 331(6023): 1390-1391. Fa, J.E., Funk, S.M. and O’Connell, D.M. (2011). Zoo Conservation Biology. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK. Honegger, R.E. and Zeigler, F.W. (1990). The 1989/1990 Crocodile surveys in European and American Zoos and Aquaria. Int. Zoo Yearb. 30: 153-157. IUCN (2002). Technical Guidelines on the Management of Ex Situ Populations for Conservation. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland. Lacy, R.C. (1993/1994). What is population (and habitat) viability analysis? Primate Conservation 14/15: 27-33. Pritchard, D.J., Fa, J.E., Oldfield, S. and Harrop, S.R. (2012). Bring the captive closer to the wild: redefining the role of ex situ conservation. Oryx 46: 18-23. Maunder, M. and Byers, O. (2005). The IUCN Technical Guidelines on the Management of Ex Situ Populations for Conservation: reflecting major changes in the application of ex situ conservation. Oryx 39: 95-98. Rao, R.J., D. Basu, et al. (1995). Population and Habitat Viability Assessment (PHVA) Workshop for Gharial. Report: 99 pp. Seal, U.S. (1993). Population and Habitat Viability Assessment Reference Manual. IUCN-SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN, USA. Soberon, R., Ross, P. and Seal, U. (Eds.). (2000). Cocodrilo Cubano Análisis de la Viabilidad de la Poblacion y del Hábitat: Borrador del Informe. IUCN-SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN, USA. WAZA (2005). Building a Future for Wildlife - The World Zoo and Aquarium Conservation Strategy. World Association of Zoos and Aquariums: Bern, Switzerland. WAZA (2009). Turning the Tide: A Global Aquarium Strategy for Conservation and Sustainability. World Association of Zoos and Aquariums: Bern, Switzerland. |

Email CSG

Email CSG