Introduction

Depleted wild crocodilian populations are usually managed primarily on the basis of conservation alone - that is, to rebuild them. The public is usually very supportive of such efforts to “help” endangered crocodilians populations to recover. However, several crocodilians are potential predators on humans and/or livestock and have other negative impacts (see below). Thus, the successful recovery of wild populations often reinstates Human-Crocodilian Conflict (HCC), leading to negative public attitudes about those same crocodilian populations for which there was support previously. For the CSG, successful conservation and management programs have resulted in recovering crocodilian populations in many countries. The challenge in many of these cases now is how to maintain those populations in the face of increasing HCC.

What is HCC?

The term “Human-Crocodilian Conflict” (like “Human-Wildlife Conflict”) is usually used to refer to damage-causing impacts of crocodilians on humans. However, here we use it in accordance with IUCN guidance to refer to situations not just where wild crocodilians threaten the safety or livelihoods of people and crocodilians are in turn threatened by human activities, but also where conflict arises between different human interest groups over possible solutions to these situations.

Crocodilians do not “make war” on humans, and using the language of conflict implies malicious intent and influences peoples’ attitudes and behaviour towards the species in question, reducing options for solutions. Framing an interaction as a conflict can polarise a situation where previously a level of tolerance for occasional negative interactions was the norm.

This in no way diminishes the importance of attacks and other direct impacts, but shifts the emphasis away from emotional reactivity to productive solution-finding. It also enlarges the list of causes and dynamics to consider beyond direct HCC impacts, because human-human conflicts over crocodilians may have important socio-economic, cultural and historical dimensions not directly related to crocodilians at all.

Thus, we use the term HCC to refer to: “any interaction which results in negative effects on human social, economic or cultural life, or on the conservation of crocodilian species and/or their habitats”. However, because HCC is most commonly used to refer to interactions between crocodilians and humans where humans or their livestock are harmed, or livelihoods are affected (eg through damage to fishing gear), that is the focus on this page.

It is important to remember that not all human-crocodilian relations are negative. There are many regions of the world where local peoples have strong and positive cultural beliefs about crocodilians, and have learned to live alongside them. Examples include sacred crocodile pools across West Africa, agropastoral communities in Benin (Kpera et al. 2014; Pooley 2017), communities in Anand and Kheda Districts in Gujarat, India (Vasava et al. 2016), Timor-Leste (Brackhane et al. 2019), some Aboriginal clans in northern Australia (Webb & Manolis 1998; Fijn 2013), the Philippines (Van der Ploeg et al. 2011), Solomon Islands (Van der Ploeg et al. 2019), Papua New Guinea (Telban 2008) and Madagascar (Pooley 2017; Zehrer 2013). Good management programs focusing on public education, prompt removal of problem animals, and the sustainable use of crocodilians have resulted in the mostly peaceful coexistence of humans with potentially dangerous crocodilian species in northern Australia (Manolis & Webb 2013; Fukuda et al. 2014), Florida and Louisiana, USA (Woodward et al. 2019; King & Elsey 2014). However, these approaches require resources that are not typically available in many other regions of the world. Each particular country or region requires policies and management programs appropriate for its particular circumstances.

Causes of HCC

Predatory or defensive bites by crocodilians on humans, livestock or pets are the main causes of HCC. Other causes include:

- competition for fish – real or perceived (subsistence, recreational or commercial fishing);

- damage to fishing gear, notably nets;

- reduced access to aquatic habitats because of the danger posed by crocodilians or through exclusion by conservation efforts;

- opportunity costs of avoiding or going around crocodilian habitat;

- lost income (or potential income) from tourism and other aquatic activities, including aquaculture, made risky by the presence of crocodilians (there are of course benefits to the presence of crocodilians too); and,

- structural damage caused when crocodilians burrow into dam walls and under roads or other structures.

Causes of HCC relating to human behaviour impacting on crocodilians (ie of conservation concern) include:

- risky behaviour in crocodilian habitat resulting from poverty and lack of resources, and/orignorance of crocodilian behaviour and biology;

- alcohol- or drug-fuelled irresponsible behaviour including deliberate provocation of crocodilians;

- killing or capture of crocodilians for commercial or non-commercial gain: for food, skins (leather), ingredients for medicine or magic, for sale or to keep as pets, pre-emptive killing or retribution because of a real or perceived threat, for sport or “fun”, or out of machismo or a desire for media attention;

- incidental capture in fishing gear and the resulting unintentional or deliberate killing;

- habitat destruction and encroachment into crocodilian habitat (construction, sand mining, tourist activities, etc.);

- competition for wild prey; and,

- water pollution and ecologically harmful levels of water extraction.

Conflicts involving crocodilians may be caused or exacerbated by factors not originating from them. For example, humans may harm crocodilians as a response directed at conservation authorities who have excluded them from protected areas designed to protect crocodilians and other wildlife.

For people like these herders in Vadodara District, Gujarat, India, crossing crocodile-inhabited waters is unavoidable. Photo: Simon Pooley.

Local communities are seldom homogeneous – there are typically differences in culture, livelihoods, beliefs, norms, perceptions, etc. Different community groups, or individuals, may have very different attitudes to appropriate management of risks posed by living alongside crocodilians. While some may demand culling or removal of crocodilians, for others the animals may have cultural significance, and removal or lethal control would cause offence. Even where animals have cultural significance, management intervention is complicated: in Timor-Leste local communities distinguish between ancestor crocodiles (harmless and not to be harmed), messenger crocodiles sent to punish evil deeds (to be tolerated), and outsider crocodiles which may be killed or removed (Brackhane et al. 2019).

In summary, while we have developed some effective approaches to the management of negative impacts by crocodiles – outlined below – there is no ‘one size fits all’ solution (Manolis & Webb 2014). Local contexts and available resources must be taken into account, and we have much to learn about the human-human conflicts resulting from human-crocodilian interactions.

Key Management Responses

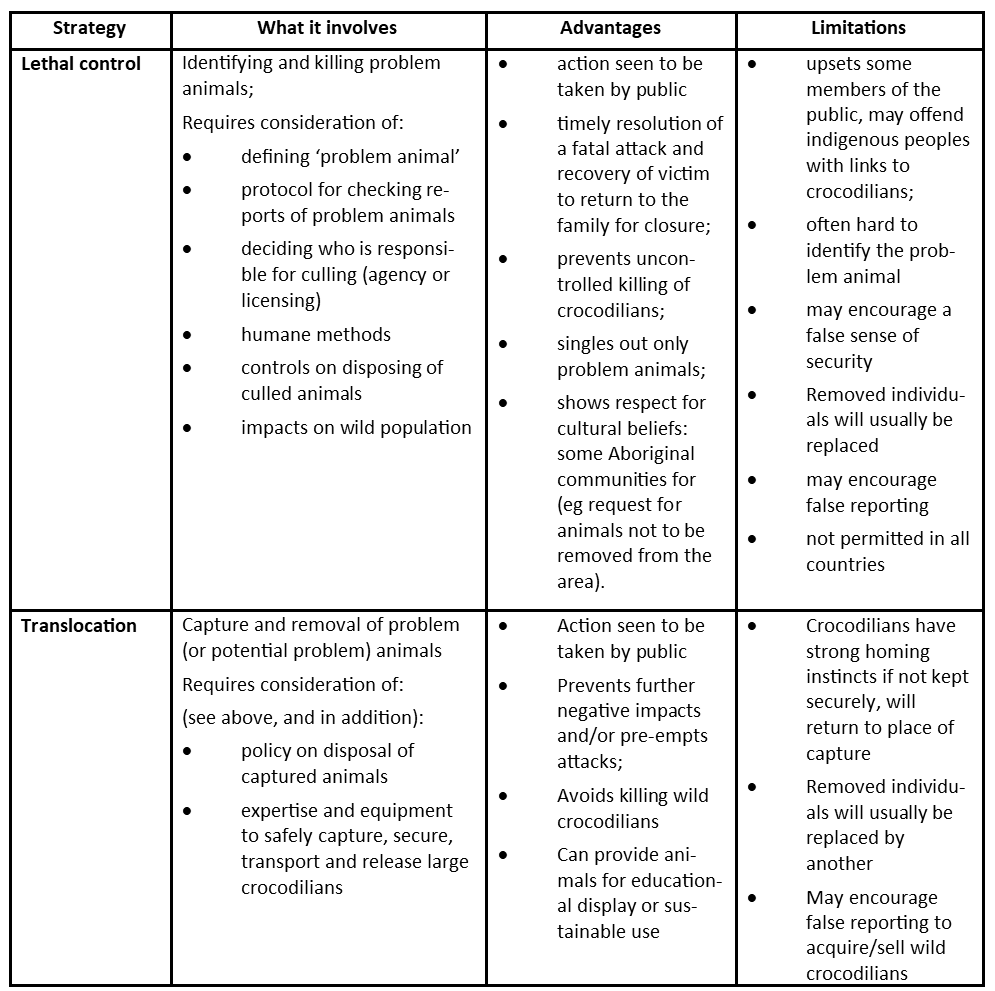

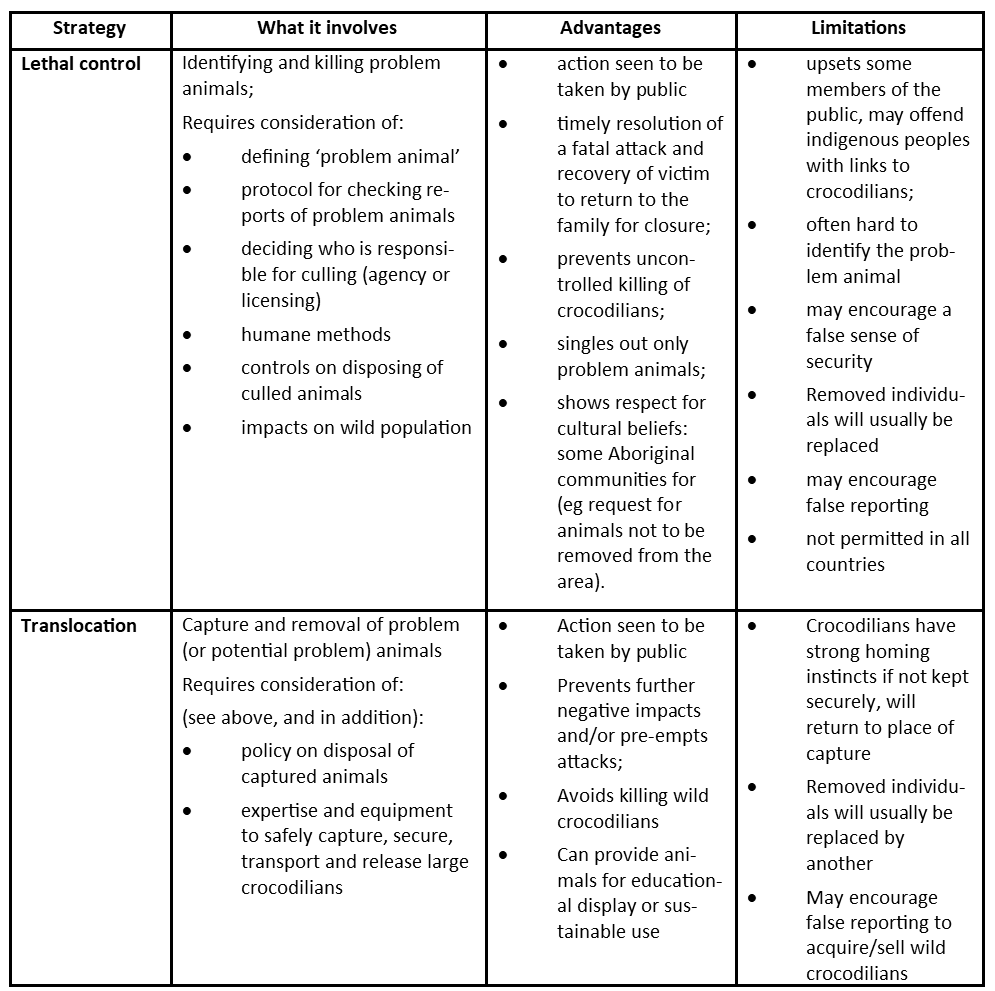

Lethal control is sometimes necessary when there is imminent danger of the loss of human life, or to prevent a major conflict and controversy detrimental to the cause of conservation. If possible, crocodilians should be captured and killed humanely away from the public and media. Where licensing and regulation are feasible (eg in the southern USA), allowing the sale of crocodilian products from culled animals may incentivise public support through economic benefits. Trophy hunting is another means of gaining conservation income and controlling problem animals, and has been successfully implemented in some countries (notably South Africa, Zimbabwe and the USA), but remains controversial in other territories. Allowing indigenous/local people to harvest problem animals (or eggs), providing this is regulated, may be preferable. Ecotourism can provide income through promoting the presence of wild crocodilian populations: both harvesting and ecotourism have promoted tolerance for wild crocodiles in the Northern Territory of Australia.

A crocodile warning sign at Shady Camp, Northern Territory, Australia - image by Brandon Sideleau

Translocation is popular but not favoured by experienced crocodilian conservationists due to the strong homing instincts of crocodilians (eg Combrink 2014; Fukuda et al. 2019) and costs. However, if crocodilians can be removed legitimately and safely to captive facilities like zoos, which have a conservation and education dimension to them, or crocodilian farms, this may be a feasible option.

Non-Removal Strategies

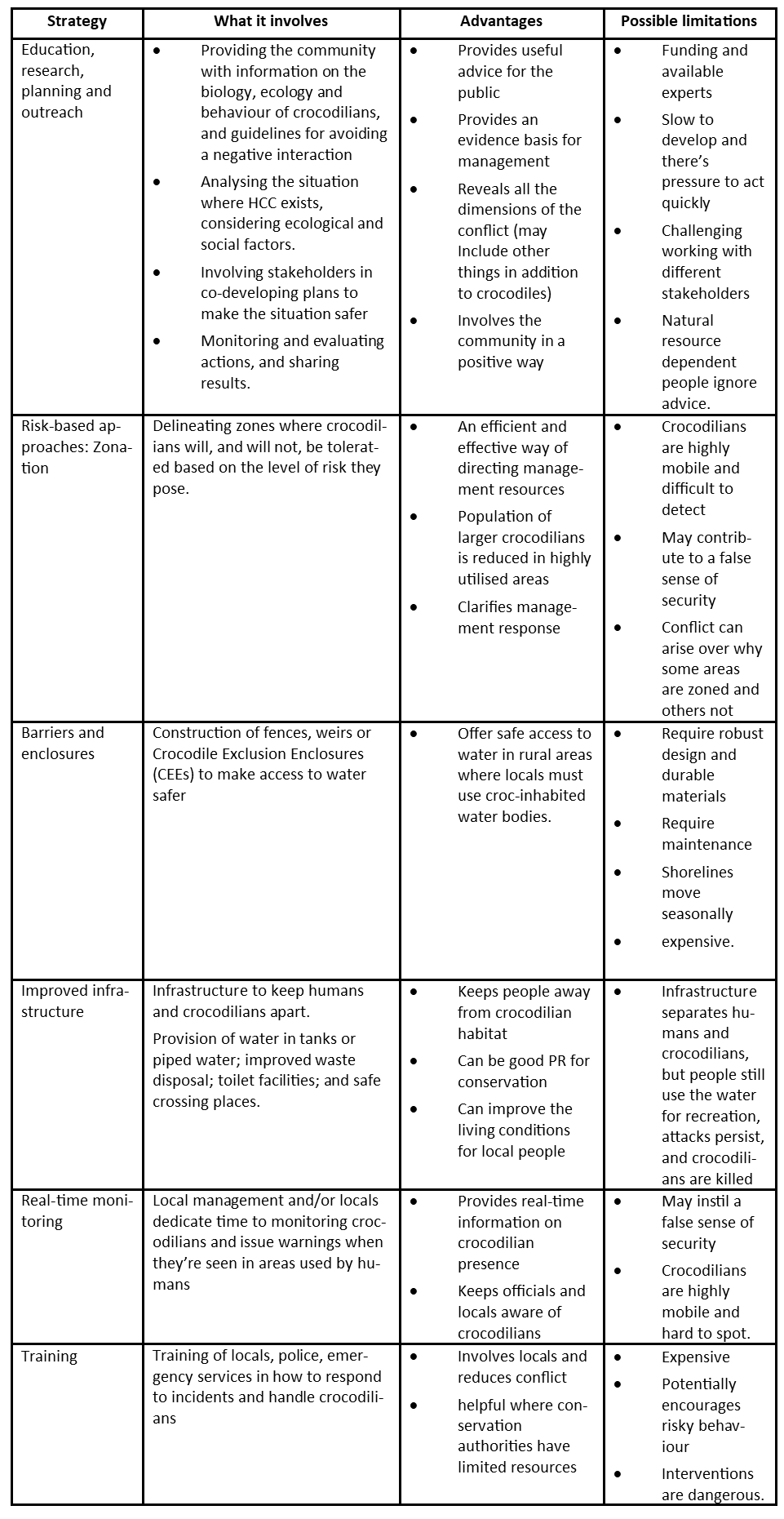

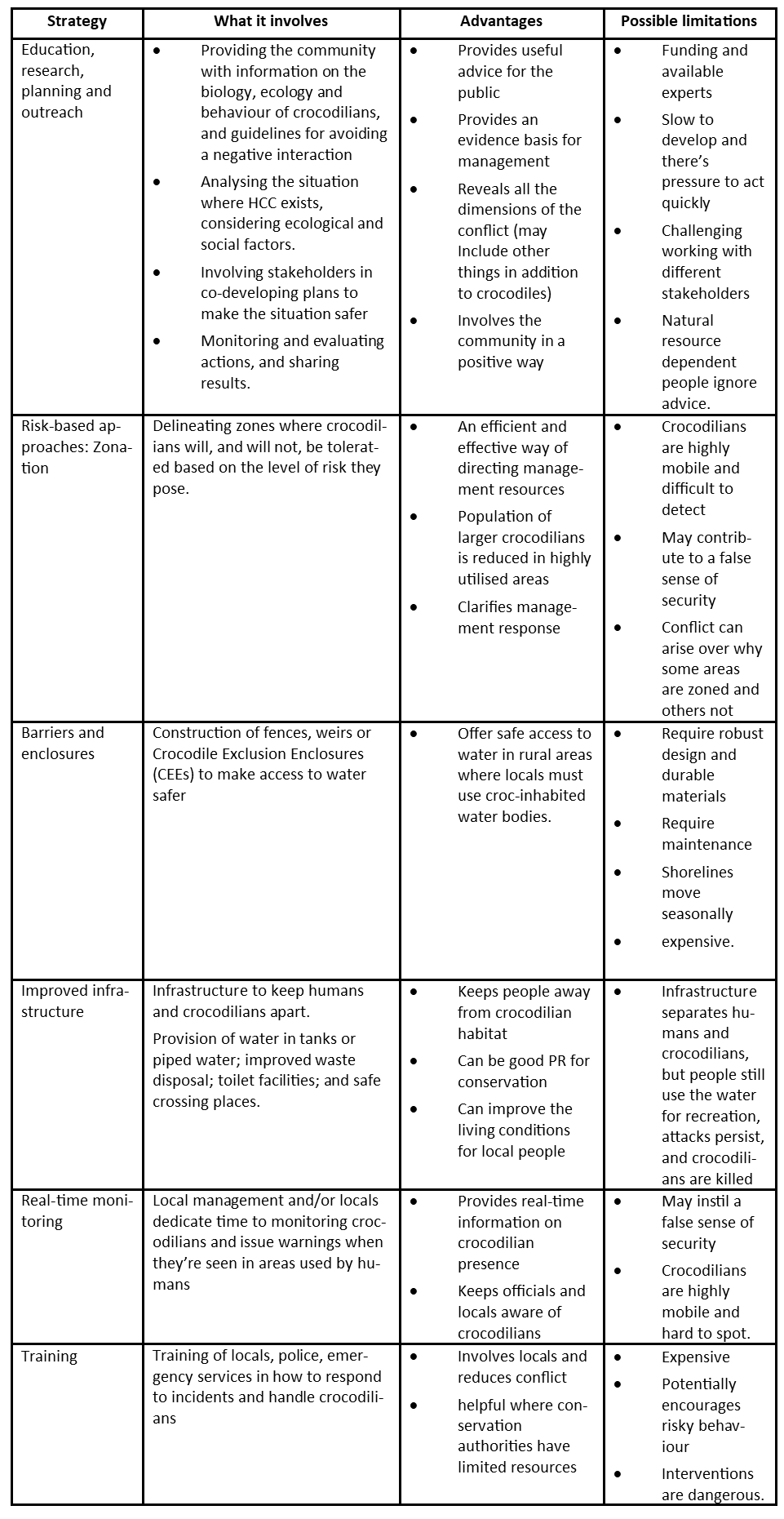

There are of course many other non-removal interventions possible. Management responses include training and funding rapid response teams which can both remove problem animals and aid victims. Access to healthcare after attacks is important, as wounds may be grievous, and infections often result. Compensation schemes can provide much needed support for victims and their families and promote good relations with communities, although they are not easy to administer.

Promoting coexistence

Long-term coexistence with crocodilians can only be achieved if the community values crocodilians, and the values outweigh any detrimental impacts of coexistence. Value can be either ecological, intrinsic, cultural, or economical (eg eco-tourism, skins). The more of these values that can be achieved or leveraged, the greater the chance of sustainable coexistence.

Many approaches have been developed to improve public awareness of crocodilians and support for crocodile conservation. These range from providing warning signs, to crocodilian safety education through talks and media presentations aimed at the general public, and schools. Several studies have looked at what influences perceptions and tolerance of crocodilians, to inform management interventions. Skupien et al. (2016) found evidence that conservation education programs can improve wildlife acceptance capacity for American alligators. Smithem & Mazzotti (2008) found that attitudes to American crocodiles in Florida were significantly related to risk perceptions and acceptance of the species, and better knowledge about the species corresponded with positive attitudes to them. Balaguera-Reina & Farfàn-Ardila (2018) found that there was a strong bias towards negative human-crocodilian interactions in reports by the media, scientific and government agencies in Colombia. This is undermining community support for crocodilian conservation in the Caribbean region of the country, and they recommend better publicising conservation projects to the general public.

Community involvement is an important area, and can include approaches like community monitoring schemes, training in observing and handling crocodilians, as well as educational talks, drama and interactive activities. Some remarkable work on this has been conducted by the Mabuwaya Foundation in the Philippines (Cureg et al. 2016), particularly as they have evaluated their interventions. Funding such programs over the longer-term can be challenging.

It is always valuable to engage with (and facilitate the sharing of) positive cultural beliefs and practices about crocodilians, and outsiders can learn from indigenous knowledge about and coexistence with crocodilians, too (Van der Ploeg et al. 2011; Pooley & Marchini 2020). Management programs should not be a “one size fits all’ solution: they should be tailored to accommodate local communities’ circumstances, beliefs and expectations where feasible.

Other approaches to promoting coexistence which have already been noted in passing include ecotourism (eg Caiman House on the Rupununi River in Guyana), and providing benefits to local communities through sustainable use of crocodilians [link to ‘sustainable use’ section].

HCC and the CSG

The IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group (CSG) was created during a period of heightened conflict over crocodilians worldwide (end of the 1960s). The eventual success of its conservation interventions resulted in recovering crocodilian populations. A resulting increase in attacks contributed to the development of conflicts over how to mitigate such situations in several key territories. Since the establishment of the CSG in 1971, numerous approaches to mitigating impacts and conflict situations have been developed worldwide, as outlined above.

In 2002, in recognition of the ongoing importance of dealing with HCC in the management of crocodilians, the CSG established a Human-Crocodile Conflict Working Group, which was headed by Richard Fergusson and Allan Woodward at different times during its period of activity (2002-2014). In 2013, an online database (CrocBITE) was set up by Big Gecko, with Brandon Sideleau, but it is now (2024) longer active.

At the 22nd CSG working meeting (Sri Lanka, May 2013), the HCC Working Group agreed to develop a resource of case studies on HCC from different parts of the world, and how communities and authorities are addressing the problem of "living with crocodilians". Several papers at that meeting dealt with HCC (eg Tisen et al. 2013; Sivaperuman & Kumar 2013; Sivaperurman & Jayson 2013; Manolis & Webb 2013; Lading 2013; Rao & Gurjwar 2013), and a special session was devoted to HCC at the 23rd CSG working meeting in Lake Charles, Louisiana, USA (May 2014) (see Woodward et al. 2014; Manolis & Webb 2014; Ponce-Campos 2014; Stevenson et al. 2014; Pooley 2014; Fukuda et al. 2014; Sideleau & Britton 2014; Carrillo-Rivera & Porras Murillo 2014). This was the culmination of the first phase of focused work on HCC. It is discussed by Alan Woodward in the Crocodilian Capacity Building Manual available on this website.

HCC continues to be a concern for the CSG, being addressed at regional workshops and subsequent CSG Working Meetings in South Africa (2016) and Argentina (2018). Since 2016, Simon Pooley has published his "Croc Digest: A Bibliography of Human-Crocodile Conflicts Research and Reports” to coincide with CSG Working Group meetings. Since the Argentina meeting (2018), ideas and information are shared through an informal Facebook group, and a standardised format for attack data collection has been developed. Work on general guidelines for responding to HCC is ongoing.

References

[For a more comprehensive list, see: Pooley, S. (2024). Croc Digest: A Bibliography of Human-Crocodile Conflict Research and Reports, 5th ed. Simon Pooley: London]

Balaguera-Reina, S.A. and Farfàn-Ardila, N. 2018. Are we ready for successful apex predator conservation in Colombia? Human-crocodilian interactions as a study case. Herpetological Review 49(1): 5-12.

Brackhane, S., Webb, G., Xavier, F.M.E., Trindade, J., Gusmao, M. and Pechacek, P. 2019. Crocodile management in Timor-Leste: Drawing upon traditional ecological knowledge and cultural beliefs. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 24: 314-331.

Carrillo, R.N. and Porras-Murillo, L.P. 2014. Human-crocodile interaction in the Great Tempisque Wetland, Costa Rica. In Crocodiles. Pp. 325-331 in Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 23rd Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland.

CrocBITE 2013. The Worldwide Crocodilian Attack Database. Big Gecko, Darwin, accessed October 2020. <http://www.crocodile-attack.info>.

Combrink, A.S. 2014. Spatial and Reproductive Ecology and Population Status of the Nile Crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) in the Lake St Lucia Estuarine System, South Africa. PhD Thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

Cureg, M.C., Bagunu, A.M., Van Weerd, M., Balbas, M.G., Soler, D. and Van der Ploeg, J. 2016. A longitudinal evaluation of the Communication, Education and Public Awareness (CEPA) campaign for the Philippine crocodile Crocodylus mindorensis in northern Luzon, Philippines. International Zoo Yearbook 50: 1-16.

Fijn, N. 2013. Living with crocodiles: Engagement with a powerful reptilian being. Animal Studies Journal 2(2): 1-27.

Fukuda, Y., Manolis, C. and Appel, K. 2014. Management of human-crocodile conflict in the Northern Territory, Australia: Review of crocodile attacks and removal of problem crocodiles. The Journal of Wildlife Management 78: 1239-1249.

Fukuda, Y., Manolis, C. and Appel, K. 2014. Management of human-crocodile conflict in the Northern Territory, Australia: review of crocodile attacks and removal of problem crocodiles. Pp. 256-277 in Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 23rd Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland.

Fukuda, Y., Webb, G., Manolis, C. et al. 2019. Translocation, genetic structure and homing ability confirm geographic barriers disrupt saltwater crocodile movement and dispersal. PLoS ONE 14(8): e0205862.

Kpéra, G.N., Aarts, N., Tossou, R.C., Mensah, G.A., Saïdou, A., Kossou, D.K., Sinsin, B. and Van der Zijpp, A.J. 2014. ‘A pond with crocodiles never dries up’: A frame analysis of human-crocodile relationships in agro-pastoral dams in Northern Benin. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 12(3): 316-333.

King, R. and Elsey, R. 2014. Louisiana’s nuisance alligator program. Pp. 163-181 in Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 23rd Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland.

Lading, E. 2013. Crocodile attacks in Sarawak. Pp. 96 in Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 22nd Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland.

Manolis, S.C. and Webb, G. 2013. Assessment of saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) attacks in Australia (1971-2013): Implications for management. Pp. 97-104 in Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 22nd Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland.

Manolis, S.C. and Webb, G. 2014. Human-crocodile conflict in the Australia and Oceania Region. Pp. 200-208 in Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 23rd Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland.

Peña-Mondragón, J.L., Garcia, A., Rivera, J.H.V. and Castillo, A. 2013. Interacciones y percepciones sociales con cocodrilo de río (Crocodylus acutus) en la costa sur de Jalisco, México [Social interactions and perceptions of the American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) on the south coast of Jalisco, Mexico]. Revista Biodiversidad Neotropical 3(1): 37-41.

Ponce-Campos, P. 2014. Human-crocodile conflict with Crocodylus acutus in Mexico, with comments on Crocodylus moreletii and Caiman crocodilus. Pp. 246-255 in Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 23rd Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland.

Pooley, S. and Marchini, S. 2020. What living alongside crocodiles can teach us about coexisting with wildlife. The Conversation, May 26. Available at: https://theconversation.com/what-living-alongside-crocodiles-can-teach-us-about-coexisting-with-wildlife-139144

Pooley, S. 2017. A cultural herpetology of Nile crocodiles in Africa. Conservation & Society 14(4): 391-405.

Pooley, S. 2014. Human crocodile conflict in South Africa and Swaziland, 1949-2014. Pp. 236-245 in Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 23rd Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland.

Rao, R.J. and Gurjwar, R.K. 2013. Crocodile human conflict in National Chambal Sanctuary, India. Pp. 105-109 in Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 22nd Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland.

Sideleau, B.M. and Britton, A.R.C. 2014. An analysis of recent crocodile attacks in the Republic of Indonesia - a case study on the utility of the CrocBITE database. Pp. 332-335 in Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 23rd Working Meeting of the IUCN–SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland.

Sivaperuman, C. and Kumar, S.S. 2013. Human-crocodile conflicts in Andaman and Nicobar Islands - a case study. Pp. 114 in Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 22nd Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland.

Skupien, G.M., Andrews, K.M. and Larson, L.R. 2016. Teaching tolerance? Effects of conservation education programs on wildlife acceptance capacity for the American alligator. Human Dimensions of Wildlife: An International Journal 21(3): 264-279.

Smithem, J.L. and Mazzotti, F.J. 2008. Risk perception and acceptance of the American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) in South Florida. Florida Scientist 71(1): 9-22.

Stevenson, C., de Silva, A., Vyas, R., Nair, T., Mobaraki, A. and Chaudhry, A.A. 2014. Human-crocodile conflict in South Asia and Iran. Pp. 209-226 in Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 23rd Working Meeting of the IUCN–SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland.

Telban, B. 2008. The poetics of the crocodile: Changing cultural perspectives in Ambonwari. Oceania 78(2): 217-235.

Tisen, O.B., Gombek, F., Ahmad, R., Gombek, F. and Kri, C. 2013. Human-crocodile issues: Sarawak report. Pp. 115 in Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 22nd Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland.

Van der Ploeg, J., Ratu, F., Viravira, J., Brien, M., Wood, C., Zama, M., Gomese, C. and Hurutarau, J. 2019. Human-crocodile conflict in Solomon Islands. Program Report: 2019-02. WorldFish: Penang, Malaysia.

Van der Ploeg, J., van Weerd, M. and Persoon, G.A. 2011. A cultural history of crocodiles in the Philippines; Towards a new peace pact? Environment and History 17(2): 229-264.

Vasava, A., Patel, D., Vyas, R., Mistry, V. and Patel, M. 2015. Crocs of Charotar. Status, Distribution and Conservation of Mugger Crocodiles in Charotar, Gujarat, India. Voluntary Nature Conservancy: Vallabh Vidyanagar, India.

Webb, G. and Manolis, C. 1998. Australian Crocodiles. Reed New Holland: Sydney.

Woodward, A., Leone, E.H., Dutton, H.J., Hord, L. and Waller, J.E. 2014. Human alligator conflict in Florida, USA. Pp. 182-199 in Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 23rd Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland.

Woodward, A.R., Leone, E.H., Dutton, H.J., Waller, J.E. and Hord, L. 2019. Characteristics of American alligator bites on people in Florida. The Journal of Wildlife Management 83(6): 1437-1453.

Zehrer, W. (2013). Le crocodile malgache, vu à travers des proverbes et contes. Edition Tsipika.

Crocodile Exclusion Enclosures (CEEs). These are used extensively in Sri Lanka, as well as parts of India - with varying success. Maintenance of the enclosures plays an obvious factor in the efficacy of the CEEs.

Email CSG

Email CSG